10/1/2012

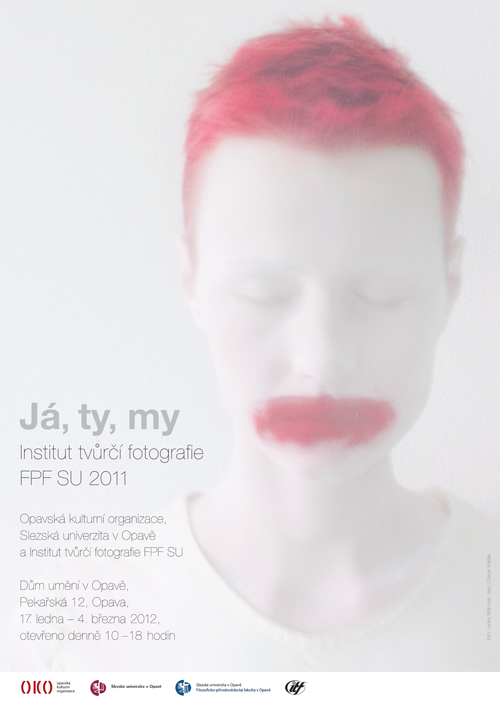

I, YOU, WE

|

The Institute of Creative Photography, the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, Silesian University, Opava, 2011

Dům umění (House of Art), Pekařská 12, Opava, 17 January – 4 March 2011. Private view on 17 January 2012 at 6 pm. Open daily from 10 am to 6 pm.

Organized by the Opavská kulturní organizace (Opava Arts Organization), Silesian University, Opava, the Faculty of Arts and Sciences of Silesian University, Opava, and the Institute of Creative Photography at the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, Silesian University, Opava. Curated by Vladimír Birgus and Aleš Kuneš.

The Institute of Creative Photography, at the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, Silesian University, commemorated the twentieth anniversary of its establishment with a large exhibition in 2010, called the 'Opava School of Photography'. It was shown in different versions in Brno, Prague, Oxford, Cologne, Bratislava, Ostrava, Liberec, Prague, Warsaw, and Vilnius (and also in a catalogue of almost 300 pages) with a wide range of photographs of various styles, topics, and themes, which Institute students and graduates made from a previous large tally in 2006. This time the Institute is presenting a far more narrow selection of the latest end-of-term, B.A., M.A. and other degree projects (all the works in the catalogue were made in 2011), on the topics of authorial self-reflection, interpersonal relations, and the family, in other words, works by means of which the photographers frequently offer the viewer a glimpse of their innermost selves and private lives.

|

| Kristýna Erbenová, Somewhere Inside, 2011 |

|

| Michaela Spurná, Summertime, 2011 |

|

| Lenka Bláhová,I am Searchingfor Myself Inside Myself |

|

| Kamila Kobierzynska, I Am Not Here, 2011 |

|

| Anna Bajorek, Casa Violeta, 2011 |

|

| Daniel Poláček, WEBsadFACES, 2011 |

Whereas in America, Western Europe, and Japan, photographers like Larry Clark, Nan Goldin, David Armstrong, Anders Petersen, Richard Billingham, Michael Ackerman, Antoine D'Agata, JH Engström, Daido Moriyama, and Nobuyoshi Araki have for a long time shown raw photos of the most intimate moments of their lives and the lives of their families and friends, in central Europe until recently this kind of open photo-diary and self-reflexive photograph has, with few exceptions, rarely appeared. In Czech, Slovak, and Polish documentary photography, topics of the 'outer circle', photos of various social groups, the devastation of the environment and of people under totalitarian régimes, and the continuing globalization and consumerism in the period after the collapse of Communism, have dominated over topics of the 'inner circle'. Few photographers were willing to stick their necks out and openly show their own private lives, uncertainties, loneliness, crises and depressions, the break-up of their families, and deviations from universally acknowledged norms. Nor, however, did positive, yet authentic, pictures of the private certainties of life, such as those provided by a harmonious family, which were intensively and unconventionally photographed, for instance, by Tina Barney, Sally Mann, and Annelies Štrba, appear often in the Czech Republic, with the exception of works by Jiří David, Bohdan Holomíček, Barbora Kuklíková, and a few other photographers. But, as our exhibition also demonstrates, that has strikingly changed in recent years.

In connection with contemporary photography, it now seems unnecessary, and indeed a cliché, to mention the transformation of the medium from the classic analogue image to the digital record that eventually occupied a striking position in the Czech Republic after 2000. Despite what many people have claimed, the means of recording is indeed relevant to the final artefact. Digital photography has opened up new areas, and not only in postproduction. It has also stripped the medium of much of the special (and slightly alchemistic) charm of the latent image. What appears on the display is a much more reliable guideline to the final result than is a role of film or a film cartridge in one's pocket. Thanks to inexpensive compact cameras and increasingly more technologically advanced mobile telephones, many more people can today take photographs than ever before.

Technological development has left its mark, however, not only on the possibilities of the photographic medium, but also on interpersonal relations, in which personal contact is increasingly substituted for by contact using mobile telephones, emails, Skype, or Web chats. In his project WEBsadFACES, Daniel Poláček focuses on the almost apocalyptic expressions of dozens of participants of a webcam chat, who for hours watch other people and sometimes try and flirt with them, sometimes exhibitionistically show off, but often only stare emptily into the camera. Entertainment becomes addiction, and hope in establishing relationships becomes the disappointment of even greater loneliness. Contact by means of the camera is considered on a far more subtle level by Joanna Ziajka in her series 4571 Minutes, in which she depicts a friend living in another town and herself in Skype conversations lasting a few hours every day.

Making often very intimate aspects public is a distinctive contemporary phenomenon that the older generation of central Europeans often finds hard to comprehend. One likely reason for that difficulty is that in the years under totalitarian regimes people concealed their private lives and masked their natural feelings in public. By contrast, for contemporary photographers it is as if there were no limits to depicting their private lives. At our exhibition that is true mainly of the works of some of the Polish students. Of many we would mention the raw, yet contemporarily poetic depictions of the ended relationships in Karolina Karwan's aptly titled work We/They and also Tomek Ratter's series Potlatch, a bittersweet visual recollection of the end of a nine-year love affair, full of subtle visual symbols and hints of narrative. Though these works, like those of Maciej Bujko, are unusually open and direct, they definitely do not contain any 'dirty little secrets'. Photographic diaries are particularly widespread today amongst young Polish photographers, many of whom, following on from others, for example, the works of Kuba Dąbrowski and Filip Zawada, now have their own blogs, in which they reveal a good deal about their lives. Photoblogs are typical of a special circle of young viewers, mostly not connected with any particular institutions, together with a different attitude to 'celebrities' who are not admired on the pages of the journals of mass culture, but are discovered in the midst of everyday life. It is true, of course, that some of the motifs or sharp contrasts of style, which are typical of them, become hackneyed by frequent repetition. Whereas in their intimate photographs the Polish students mostly prefer strict authenticity, their Czech and Slovak fellow students more often use carefully thought-out staging. An example of a picture diary in the style of 'photographic archaeology' with a new interpretation of old photos is the degree project Cheap Jokes, which Libor Fojtík has compiled from snapshots of various practical jokes played by himself and a group of friends to escape the mind-numbing boredom of the small town where they attended secondary school.

The transformation of the traditional family in central Europe has to be seen together with the transformation of the 'public space' in the four decades under the totalitarian régime, which ended in late 1989. Most of the young photographers with works in this exhibition know the reality of Communism from early childhood or, more often, only from the accounts of older relations and friends or from books and films. It is all the more surprising, then, how superbly Anna Gutová and Gabriel Fragner have managed in the series I Love My Family to imitate the period atmosphere of family photographs from the years of hard-line Communism reinstated with the ‘normalization' policy of the régime led by President Gustáv Husák. To achieve superb stylization they have used the faded colours of old Polaroid photos and the inventive installation of photographs in period frames on a wall covered with patterns applied by paint rollers. Their witty reconstruction of photos of a happy young family from the 1970s was rightly the winner in this year’s Frame competition. The set also symbolizes the confusion of children when gradually discovering the bygone world of their parents. In this game one can develop a dialogue that is a fascinating commentary on the times of their parents' youth.

The exhibition of course also has more traditional pictures of contemporary families, for example the artistically refined portraits of close relations by Krzysztof Kowalczyk or Tomáš Trojan's characteristic photos from the lives of his ageing parents, who were left alone after all four of their children had moved away. In his series, Trojan has truly succeeded in showing, as he himself states, that 'a married couple, not quite sixty years of age, tired of work and tired of each other, live together in a big flat yet really live only next to each other, passing each other by, yet needing to feel that the other person is still present at home.' Kristýna Erbenová's photographs from the Somewhere Inside series depict family members and friends in moments separated from the surrounding world, in contemplation, in moments between waking and dreaming. They exude a subtle melancholy, which is intensified by muted colours in a minor key. In the series Julia Wanabe, Anna Grzelewska has systematically made extraordinarily powerful photographs of her own daughter. In them she has superbly captured the world of a girl between childhood and maturity. Combining authentic and staged photographs, she draws inspiration from Romanticism. Typically, this series is made of individual 'scenes’, which (like recollections of childhood) provide an opportunity for psychological analysis. Michaela Spurná, who is also orientated to photographing her children, says about her still unfinished Summertime series, which accentuates family values: 'A few moments from my childhood come to mind, but mainly the fragrance of the washing on the line in our garden, the smell of fish after swimming in the pond, various smells of farm animals. It's very likely that most of today's children when recalling summertime will recall the smell of fabric softener, chlorine from the swimming pool, and, instead of hay, the smell of a freshly mown lawn'. Strong family ties and intergenerational relationships radiate also from the classic black-and-white documentary photographs in the Czech-American Andrew Jan Hauner's series, My Prague Grandfather. A far more expressive form for depicting her grandmother's life was chosen by Ewa Dyszlewicz in the series I Remember Everything, I Forgot Everything. In the mosaic of portraits, documentary photos, and fragments of a milieu in his series A Place Called Home Rafał Siderski shows the return of a woman who, after years living in Cyprus went back to Poland to spend Christmas with her close relations.

In addition to family members, friends of the photographers and the photographers themselves also appear in many of the exhibited photographs. A characteristic feature of some of the works is the oscillation between the directness of the Web, inspired by the literary styles of the blog, and a new form of staging, fusion with the documentary (for example, the series Don’t Live Alone by Krzysztof Pacholak about a group of student flatmates, and Anna Bajorek's La Casa Violeta series). Daniel Laurinc combines snapshots and portraits of his girlfriend with metaphorical photos of static objects. In her staged portraits from various milieux, Magdalena Cónová has depicted her partner and expressed her relationship with him. In the series I’m Not Here, Kamila Kobierzyńska has depicted her near and dear ones by means of diptychs of photographs, juxtaposing portraits of them and fragments of the interiors in which they live. In Near and Dear Ones, a set with a similar theme, Hana Pokorná has staked even more on pairs of photographs. By contrast, in his Good & Evil series, Dereck Hard has made use of at times theatrical staging, depicting himself and his friends in the roles of 'good guys' and 'bad guys'. In this way he suggests that everyone has a Doctor Jekyll and Mr Hyde inside and that people’s characters are not necessarily connected with the way they dress or the number of tattoos or piercings they may have. On the other hand, Roman Dobeš, in the series The Right One, photographed each of his models (including himself) a hundred times at negligible intervals and with inconspicuous changes of facial expression, eventually choosing a single portrait from each set. He leaves it up to the viewer to decide whether it is the selected photos that best capture the essence of the person in front of the camera. The photographers themselves are featured in a number of photos at the exhibition. The self-portrait as a form of self-reflection is of course nothing new in photography – recall, for instance, the works of Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz or Claude Cahun. Among the works of Institute of Creative Photography students we encounter various forms of self-portraiture. In Kamila Rokicka's series, Memory Stick, we arrive at the heart of the direct experience of the birth of a new life. In her series of strikingly stylized and tonally modified self-portraits, I Am Searching for Myself Inside Myself, remotely reminiscent of paintings by Renaissance masters, Lenka Bláhová has created a distinctive combination of autobiography and art therapy: 'The closed eyes in the cycle of experienced emotions, where nothing is black-and-white. The synthesis of two levels – the outer, visible, positively existing, and the inner, unexpressed and unexpressible, merely sensed.' In exposing her private life, Magdalena Veselá has truly gone right to the core. She made the photographs and videos of her Should I Stay, Should I Go? series at the time she was trying to decide whether to remain in her marriage or solve the crisis in her relationship and the difference in interests and values by leaving her husband. The work was given another dimension by the fact that she has also given space to photographs by her husband, who saw many situations differently.

Though it includes a number of striking works representing several current trends in the choice of topic, subject matter, and style at the Institute of Creative Photography at the Faculty of Arts and Sciences of Silesian University, the exhibition 'I, You, We' represents but one current in the far richer spectrum of art photography at our school.

Vladimir Birgus and Aleš Kuneš

(Translation: Derek Paton)