1/7/2011

Czech Photography od the 20th Century

|

| Czech Photography of the 20th Century.cover |

Vladimír Birgus, Jan Mlčoch: Czech Photography of the 20th Century. Graphic design - Vladimír and Martin Vimr. English translation - Derek and Marzía Paton and William McEnchroe. KANT (Karel Kerlický), Prague 2010. 390 pgs.

Writing history is a big responsibility, as long as we still believe in the power of words, as long as we are convinced that what we’re writing is not irrelevant, and that culture (civilisation) without words would cease to exist. And that the inflation of words means the devaluation of culture. Sometimes I believe that this is the minority view – not that it is fully destined for extinction – but rather that it’s been pushed aside. Pressure for quick results, and if possible immediate effect, results in nothing being prepared well and the public demanding various ready-made goods.

|

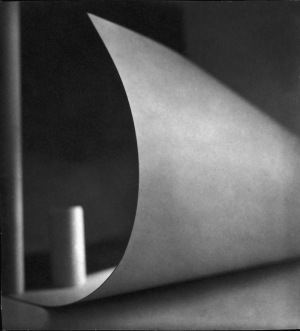

| Jaroslav Rössler.Untitled II, 1923 |

|

| Eugen Wiskovsky, Disaster, 1939 |

|

| Svatopluk Sova, German Women Paving the Streets of Prague, 1945 |

|

| Josef Sudek, The Last Rose, 1956 |

|

| Běla Kolářová, Signs, 1964 |

|

| Ivan Pinkava, Narcissus, 1997 |

Fortunately there are still areas where omnipresent relativisation has not yet intervened, where everyone can say or write anything – and with the end result it is more or less irrelevant whether anything serious or binding exists. Perhaps more exact than sphere one should say that there are personalities, who refuse such an approach and in their works back the belief that their view of history must still be based in fact, in interpretations, that are not „drawn out of thin air“ but which place emphasis on context, on the detailed knowledge of the work reviewed, on personalities and events. Vladimír Birgus and Jan Mlčoch, co-authors of an impressive history of Czech photography in the 20th century rank among these „conservatives.”

After 1989 Czech photography made a significant mark on various exhibition and literary activities in the European, and also the American, context. (This is very well documented in the appendix to the Chronology of Czech Photography in the 20th Century by Vladimír Birgus, who points out the most important events of the entire century). Even in the domestic context, the number of books on photography, schools, and galleries that focused exclusively – or to a larger degree – on photographic work grew profoundly. However, one weak point was – among the books on Drtikol, Rössler, Sudek, etc. one fundamental book was missing – a text on the history of Czech photography. Meanwhile, to say the least, one would have expected that after the publishing approach of Daniela Mrázková and Vladimír Remeš in the book, Cesty československé fotografie / The Paths of Czechoslovak Photography (1989); in this book the concept of so-called Czechoslovak and not Czech or Slovak photography still functioned – that Anna Fárová and possibly or Antonín Dufek were authors, who could have taken on this role. Yet neither of them did (even if Dufek wrote texts on photography for the book, Dějiny českého výtvarného umění / The History of Czech Creative Arts. The „Achilles heel“ of the history of Czech photography remained: until their successors filled the gap.

Vladimír Birgus (1954) and Jan Mlčoch (1953) arrived at working on a history book after several years‘ preparation. Both had published many texts on exceptional personalities in Czech photography, they had prepared a number of collective exhibitions. But the most important thing was their Prague exhibition in 2005 – Czech Photography in the 20th Century (later reprised in Bonn in 2009) for which they published a guide – an outline of the book they would later write. (To complete the characterisation of these historians it is necessary to mention that both are dual-disciplined: Vladimír Birgus is still today an important photographer-documentarian and Jan Mlčoch ranked among the key personalities of Czech action art in the 1970s).

The book, Czech Photography of the 20th Century, is divided into 17 chapters. Their titles alone indicate that the authors were not interested in some sort of pseudo-scientific terminology. They chose an aesthetic language, accessible to the broader public, yet still not deforming the researched topic. The authors divided the century into watershed years – 1918, 1939, 1948, 1968 and 1989 – i.e. into six periods. The titles of the chapters capture their ideas on their views of the transformation of tendencies and on the dominant trends in this or that period: Pictorialism; Documentary Photography and Photojournalism up to before 1918; From Pictorialism to Modern Photography; Poetism and the Beginnings of Abstract Photography; New Photography – Constructivism, Functionalism, and New Objectivity, Social Photography and the Beginnings of Modern Photojournalism and Social Photography; Surrealist Photography and Collage; German and Austrian Photographers in the Czech Lands; Documentary Photography and Photojournalism during and after the 2nd World War II and After; From Surrealism to Glamour Photography; From Socialist Realism to Humanist Photography; Traditionalism, Imaginative Photography, Lyrical Tendencies, Surrealism, Art Informel and Staged Photography; From Humanist Photojournalism to Subjective Documentary Photography; Conceptual, Land, Body, Action, and Performance Art Art, Happenings, Land Art, Performance; From Minimalism to Postmodernism; Photojournalism and Documentary Photography after 1989; Photography at the Beginning Start of a New Era.

The text can be typified by its good proportion in combining amounts of factual information with accurate characterisations of personalities, tendencies and works of art. Essentially there is no break in any of the chapters that would draw attention to the fact that it was written by two persons. One can also rely on the facts recalled having been verified and not just borrowed from someplace. They are backed up by either private or public archives.

Even if the book is truly comprehensive; on the other hand, it is also economical. Each chapter is a short of expanded encyclopaedia of key words. The authors take care not to overwhelm the reader with too many details so that he/she doesn’t get lost in mountains of information. They reliably guide the reader on a journey through Czech photography and Czech culture and society of the 20th century. For the book’s structure its inventive graphic design is fundamental. Its excellently printed image sections are an integral part of the text. The authors were able to collect truly decisive works from the creations of individual artists (more than 500 photographs). So the text is not just some sort of abstraction, but it is also possible to determine from used images to what extent the formulations therein are or are not in agreement with what the critiqued photographers created.

Also the book is not just a list of famous persons. It delves into the history of names and works that are the results of only recent discoveries. Among these contributions we must rank the inclusion of photographs from the legacy of Jindřich Bišický from World War I, or the works of Gustav Aulehla, Miroslav Tichý or the series on military service at Mošnov by Josef Moucha. We also consider beneficial the fact that the book also contains chapters on conceptual art, on creation at the limits/borders of photography and contemporary Avant-Garde. This is a decision that would have been unimaginable ninety years ago – that together with a discussion on the works of Josef Sudek, one could also recall Jiří Valoch, Milan Knížák or Jaroslav Anděl.

The same goes for the inclusion of German, and also Austrian and Slovak photography, created in the Czech lands, into a history of Czech photography. This is a legitimate decision: dialogue between various traditions belonged to important moments in Czech photography. It wasn’t always intensive, but it did always exist to some degree. Their recollection of the dispute over who took a photograph of the German Army’s occupation of Prague in 1939 only underscores the fact that sometimes it is not always obvious and easy to classify one work or another. When they decided that the photograph was most probably the work of Josef Novák, they sent a signal to future historians not just to accept long-held opinions, but rather to verify critically just as Vladimír Birgus and Jan Mlčoch did.

Just as the scope of the book moves from Pictorialism to conceptual photography, it is also important that the authors devote space to commercial (advertisement) photography. It is of foremost importance that they don’t just view the history of photography as that of big changes and big personalities, but rather they follow photography as part of visual anthropology. Photographs by anonymous authors, i.e. those taken during the events of the liberation in 1945, sometimes rank about the most extraordinary messages. These are ones in which the photo’s author photographer seems to move into the background and the record of the event itself is most riveting. Even the reproduced propaganda photos for the 1950s give an accurate testimony to a period when executions took place and when Communist totalitarianism definitely conquered society.

When reading the story of Czech photography it is important that both authors take notice of the close connection between their photographs and the actual events in other European photographic cultures – and this regardless of whether it concerns Pictorialism, Surrealism or subjective photography. The transformation of Czech photography did not occur alone on its own island or for its own sake, but rather was part of a broader movement that more or less had a parallel impact on various European photographic cultures.

What’s nice about the book is that its authors represent a clear stance on values; i.e. just as they criticised Anna Fárová for ignoring the works of Viktor Kolář, still it is not their ambition to provide a list of names of all persons who created Czech photography during the past century. They report on key personalities, on decisive trends, on that which today is still alive and current. You will most definitely find readers, who could say for example that Jan Saudek should have received more space than Antonín Kratochvíl. But then the book would be completely different. Both authors have made a sensitive, balanced and responsible selection of what, according to them, has lasted.

When after 1989 there was a constant reminding that Czech culture needed a history of photography; that after sixty years of black, or more accurately red, totalitarianism it is possible to write a book without an ideological dictate, every year without said history seemed for historians of photography to be a wasted one. But on the contrary it was worth waiting for Czech Photography of the 20th Century. The resulting book gives a valuable, balanced and meanwhile convincing view of one-hundred years of creative work in the Czech lands. It will definitely be, for a long time, a reliable guide to understanding all that took place in Czech photography during the past century.

Václav Macek

Zdroj: Fotograf, 2010, č. 16