26/10/2009

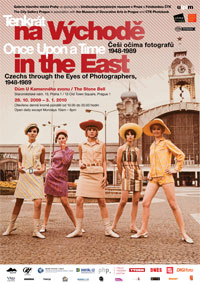

Once Upon a Time in the East

|

| Once Upon a Time in the East.poster |

Czechs through the Eyes of Photographers, 1948–1989

The City Gallery Prague, The Stone Bell House, Straměstské náměstí 13, Prague

28 October 2009 – 3 January 2010

Exhibition curators: Vladimír Birgus, Tomáš Pospěch

Architectural concept: Emil Zavadil

Graphic design: Vladimír a Martin Vimr

The exhibition has been organized by the City Gallery Prague

in association with the Museum of Decorative Arts in Prague,

the CTK Photobank, KANT Publishers and the Institute of Creative

Photography, Silesian University in Opava.

Catalogue: KANT (Karel Kerlický), Prague – www.kant-books.com

|

| Věněk Svorčík, ČTK Photobank, Voluntary Workers, 1950 |

|

| Erich Einhorn, Morning in Prague Tram,1956 |

|

| Jaroslav Kučera, Strahov Student Dormitories in Prague, 1972. |

|

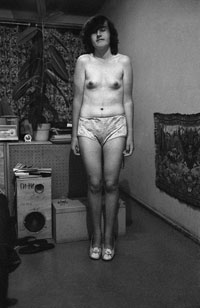

| Jindřich Štreit, Sovinec, 1982 |

|

| Lubomír Kotek, from the series Signs, 1980s. |

|

| Josef Moucha, from the series Army raining ompany, Mošnov 1982 |

|

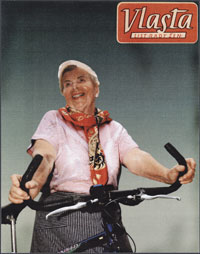

| Martin Plitz, from the series Women from the Title Page of Vlasta Magazine, 2000 |

The exhibition Once Upon a Time in the East: Czechs through the Eyes of Photographers, 1948-1989, is neither a historically relevant image of life in Czechoslovakia during the Communist regime from its establishment in 1948 to its demise in 1989, nor an attempt to cover all the main trends, photographers, critics, as well as works of Czech documentary photography of this period. By presenting well-known, forgotten, and also hitherto unpublished photographs, it seeks to show aspects of the lives of ordinary people in Czech lands at the time, when one was required to do so much and permitted to do so little. With selected examples from a broad range of photos of varying artistic quality, the exhibition seeks to show the changes in the political and social atmosphere, and way of life, as well as to show official Communist festivities and demonstrations, the ubiquitous ideological propaganda and the devastation of both society and the environment under single-party rule. It also aims to show how many people escaped into their private lives, pubs and cottages, where less official, but more truthful and spontaneous life took place.

Both the book and the exhibition feature samples of official agency photographs from the photo bank of the Czech Press Agency (ČTK), period fashion and advertisement shots, photographs promoting the famous Unified Farmers’ Cooperative in Slušovice, and even shots clandestinely taken by the secret police (StB) when monitoring dissidents, people considered dangerous to the régime, and foreigners. The backbone of the exhibition, however, is formed by thematic sets of works by well-known, forgotten as well as totally unknown Czech photographers. Many are published here for the first time.

After the Communist takeover in February 1948 all Czech photography underwent profound changes which influenced it for decades to come. Photographer-tradesmen had to register in cooperatives just as free-lance photographers had to be registered in the artists’ union. Many magazines ceased to exist. Heavy censorship began to be applied. The régime required the dogmatic application of the principles of Socialist Realism and the social and propagandistic function of photography, ideological involvement, an optimistic approach, transparent traditional composition, with subject matter that could be understood by the masses. The range of subjects of officially published photos was highly restricted; a truthful representation of reality was superseded by a pleasing idealized image of the new régime. There were repeatedly the same arrangements elaborated to the most minute detail, featuring the efforts of the builders of Socialism, the happy days of young pioneers and members of the Czechoslovak Union of Youth, the vacations of the working people in trade-union recreation facilities, celebrations of Communist holidays, Communist Party congresses, meetings and training sessions, the establishment of the Unified Farmers’ Cooperatives, staff meetings dealing with work plans and commitments, the determination of the soldiers of the Czechoslovak People’s Army to defend their homeland against the imperialist enemy, and the achievements of Socialist sport. We know most of Czech photographs in the style of Socialist Realism only from periodicals of the time, since most of the originals have been lost. Fortunately, the ČTK photo bank, a kind of ‘pictorial memory of the nation’, contains many official shots from that period, including sad evidence of the show trials, in which dozens of innocent victims were convicted to years in prison, and sometimes given death sentences.

Only a few leading photographers had the courage of Jan Lukas at the time of the harshest Stalinist régime in Czechoslovakia, from 1948 to 1953, to record the suppressed expressions of the desire for freedom and the typical images of the time. Most photographers took non-ideological photos. Fortunately, after the death of Stalin and Gottwald in 1953, there was, in connection with mild political détente, a gradual departure from Socialist Realism. The heroism of major social themes in the late 1950s was gradually replaced by the interest in everyday events. The ‘poetry of everyday life’, which began to appear ever more distinctly in Czech literature, film, sculpture and painting of the time, also found its place in photography. Its representatives in our exhibition and book, for example, Václav Jírů and Erich Einhorn, tried to make transparently composed and easily understood photos, which emphasized the lyrical and often humorous moments of everyday life. They mainly appeared as genre illustrations in dailies and magazines. But beginning in the late 1950s they were frequently published in books as well. An original example is the publication by Milada Einhornová, Rickys Abenteur in einer grossen Stadt (Ricky’s adventure in a big city, 1958), featuring the bizarrely staged adventures of a nanny-goat who moves about on her own in Prague.

A strong impulse for the development of Czech photojournalism and documentary photography was the publication of Anna Fárová’s book about Henri Cartier-Bresson in 1958. His conception of humanistic photojournalism, capturing the ‘decisive moment’, together with works by other leading members of the Magnum Photo agency became a model particularly for the young generation of photographers. Some of its representatives, such as Jiří Všetečka and Pavel Dias, took a number of shots of everyday life, which have remained relevant to this day. The new magazine Mladý svět (Young world) provided an opportunity to publish several-page photo essays from the life of young people as well as snapshots from various parts of Czechoslovakia and travels abroad. A good example is the series Tramping, in which Miroslav Hucek considers the then typical phenomenon of gradual political and social thaw, when tens of thousands of young people, influenced by the tradition of the First Republic and their admiration for American culture, escaped together with their friends to ‘tramping’ settlements in the countryside every weekend. Mladý svět was, however, the official weekly of the Czechoslovak Union of Youth, so despite the freshness of its photography it contains hardly any really critical views of society under single-party rule.

This, by contrast, can be found for the most part in works by several prominent amateur photographers who did not care whether their photographs might not be found ideologically acceptable or might not be published or exhibited. An exceptional body of work was made by Gustav Aulehla, who was hitherto almost unknown. His raw, authentic, generalizing shots of life in the small town of Krnov from the late 1950s onward, capture absurd and grotesque elements of official Communist celebrations, the loss of individuality of people in the crowd, and the contradiction between the optimistic slogans of propaganda and the harsh reality. At the same time, they aptly and often subjectively show the private sphere, which the régime had failed to destroy. A more lyrical ring is to be found in the photos of everyday life by another long-ignored amateur photographer, Miloslav Kubeš. The same applies to the magical and slightly ironic photos from funfairs and carnivals by the photographer-architect Ivo Loos. We also find wonderful documentation of that time in the archives of many other amateur photographers, such as the fifty-year-old unrefined photos from a huntsmen’s festival, which were taken by Rudolf Jarnot. And we find it in the bequest of the practically unknown Josef Kohout, who made his living as a photographer after being released from a Communist prison, but who was not permitted to publish his bitter photos taken in Prague streets. In his first mature shots from life in the industrial city of Ostrava, taken in the late 1960s, Viktor Kolář was often uncompromising in revealing the devaluation of ethics, while being poetic in his discovering phantasmagorical moments of everyday life.

The pinnacle of Czech documentary photography of the 1960s is undoubtedly the oeuvre of Josef Koudelka. This is evident not only in his series Gypsies, but also in his series of visually strong, objective, and generalizing photographs from the Soviet occupation of Prague in August 1968. These photos show the resistance of defenceless people to armed violence, as well as their solidarity, hope, despair, and delusion. Miloň Novotný’s photographs of the funeral of Jan Palach, the student who set himself on fire in the centre of Prague in January 1969, became a symbol of the last major protest against the concessions the Czechoslovak leadership was making to the Soviet forces of occupation.

In the period of ‘normalization’ policy, after Gustáv Husák became the First Secretary of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia in April 1969, hard times set in also for photojournalists. Amongst the photographs in periodicals, obligatorily optimistic works not seeking broader contexts or with little ambition to reflect their photographers’ own styles again began to dominate. The situation in documentary photography, on the other hand, was far better. Such photographs were usually not made on commission, and therefore had little chance of immediate publication in the press or in books or of being shown at exhibitions. Consequently, people making such works had great creative freedom to depict the difficult period with honesty. Some of them (for example, Ivo Loos, Dana Kyndrová, Gustav Aulehla, and Viktor Kolář) used this freedom in ironically conceived photographs capturing the absurdity of mass celebrations of May Day and other holidays, Communist iconography, and the bleakness of life in ‘real Socialism’. Jindřich Štreit made raw, sometimes almost surreal pictures of rural life in the difficult conditions of the Bruntál region near the western frontier of Moravian Silesia. In his photos, so removed from the idealized picture of the village presented in the state-controlled communications media, he did not conceal his romantic view of society or his humanist admiration for traditional human values. But he also observed the creeping consumerism, the arrival of television in the traditional milieu, alcoholism, the break-up of families, violence, and the destruction of the environment and of traditional rural values. A unique, effective set of documentary photographs about a squad in the Czechoslovak People’s Army in Mošnov, a suburb of Ostrava, was made by Josef Moucha. It shows them being drilled, brainwashed, and having their dignity tread on, but it also shows more pleasant moments outside barracks. It was not published till twenty-seven years after he made it.

We do not find even a hint of idealization in the works of Ivo Gil, which were taken in an institution for mentally retarded children. This is not, however, naturalism for its own sake. Rather, it is testimony about the coexistence of handicapped people and self-sacrificing nuns, two groups that the régime intentionally kept on the margins of society. In the Seventies, Together with Markéta Luskačová and Pavel Štecha, Gil was a pioneer of Czech sociological photography. Of this trio, however, only Štecha devoted himself to working with sociologists over a long period, creating austere, pithy, compositionally simple, though somewhat cold sets of photos as illustrations to various research projects. Štecha influenced many FAMU students, and some of them used the sociological eloquence of static objects that revealed much about people without their actually being there. In the set Windows, for example, Jaroslav Bárta juxtaposed the remains of original facades of old houses with their insensitive, even brutal remodelling. His photos of bricked-up, ‘silenced’ windows contain not only a reflection on the passing of time, but also the inseparable political subtext. Their effect is similar to that achieved in Jiří Poláček’s ghostly night-time photos of fragments of the Smíchov district in Prague. An even more damning accusation of the régime, which in 1985 did not hesitate even to demolish the architecturally valuable Praha-Těšnov railway station, is provided by Jaroslav Kořán’s ghostly photos of the ruins of this building. In his large set Signs, Luboš Kotek shows the ubiquitous Communist propaganda, which was posted along motorways or in shop windows, full of the ‘soc-art’ of hammers and sickles, five-pointed stars, and portraits of ‘statesmen’ visiting the prefab concrete jungles of housing estates where everything was the same. Jiří Hanke, in turn, used his beloved time-lapse method to compare subjects photographed over longer periods of time, as in his set of photographs of Váňova street in the steel town of Kladno from 1981 to 2001. Here, using the example of one building on a corner, he eloquently illustrates the revolutionary changes in society.

The private lives of most people in ‘real Socialism’ were radically different from what they had officially been portrayed to be. People escaped into the psychological security of their homes and weekend cottages; they focused on bringing up their children, chatting with their friends, going to pubs and football matches, watching television series, going on excursions, playing sports, and having sex. Many photographs show that life in those days was not so grey and full of anxiety as may appear from today’s point of view. Jaroslav Kučera in the early Seventies photographed students’ wild parties at the Strahov dormitories in Prague. In depictions of small-town life, Gustav Aulehla has photos even of very intimate moments. Using a primitive camera he cobbled together himself, Miroslav Tichý surreptitiously made blurry photos of women at the public swimming pool, in shops, and on the streets of the south-Moravian town of Kyjov. With their anti-aesthetic and technical imperfections, Tichý’s work is quite different from any of the contemporaneous trends in Czechoslovak photography. The photographs by František Dostál from the series Summer People, full of beer-hall wisdom, humorously show moments of relaxation by a river, but the subtext warns against the decline in life’s values. Zdeněk Lhoták in the series Sparta Prague created a many-layered view of football and its fans. Jan Jindra, in 1982–84, made picturesque photos of New Year’s celebrations in the Hotel Jalta, Prague, depicting performances by a variety of prestidigitators, scantily clad women dancers, and people dressed up like characters from the fairy tales on Czech television. Similarly, Libuše Jarcovjáková photographed the T-klub in Prague, using, against the aesthetic canons of the day, the harsh light of an electronic flash. Without visual embellishments, she photographed this famous nightclub, winning the trust of the homosexual men and women who used to meet there. The apparent freedom of this milieu, however, was often under surveillance by the secret police, just like the many events held by underground painters, sculptors, and musicians, which are documented by Helena Wilsonová. On practically a daily basis, Bohdan Holomíček, expanded his distinctively personal photographic diary, in which, apart from self-portraits, photos of his family, and the countryside he has driven through, includes photos of theatre performances and concerts held without the approval of the Communist authorities, and also spontaneous snapshots of meetings of dissidents.

In the Eighties, mainly after the introduction of Gorbachev’s perestroika and glasnost, it was becoming clear to some people that the totalitarian system was getting weaker. More and more people were finding the courage to take a critical attitude towards the artificially maintained régime and to seek alternatives to the existing two-faced approach to life. In his generalizing photographs from the late Eighties, Václav Podestát depicts the final round of the Porta festival competition, Pilsen, where tens of thousands of people used to meet to enjoy moments of togetherness and freedom while listening to live folk and country music. Karel Cudlín photographed the westward exodus of East Germans by way of the Embassy of the Federal Republic of Germany in Prague in summer 1989. Several months later the Velvet Revolution helped to end one-party rule in Czechoslovakia. That was also contributed to by the photographs of Radovan Boček and Pavel Štecha, which were distributed in mass print-runs. While the state-controlled communications media were either keeping silent or outright lying about events, these photos showed what had really happened during the brutal beatings of demonstrators by the riot police on Národní třída in Prague and during the first big demonstrations.

With the return of democracy Czech photography again underwent considerable change. Many photographers lost their main subject of ‘opposition’ to the régime. But for others the era of totalitarianism again became an inspiration for work outside documentary photography. In their staged photographs the group Bratrstvo (Brotherhood), in the late Eighties and early Nineties, exploited themes from Communist iconography. Martin Plitz also started from themes of the Communist era, reconstructing the sentimental heroism of women depicted on the covers of Vlasta magazine in those days. Many years later he sought out the same women who had posed as lathe operators, pilots, architects, and journalists, and photographed them in the same settings as the staff photographers on this women’s weekly had once done. It was as if the pathos and heroism of Socialism had never ended.

As the forty-one years of single-party rule recedes increasingly farther into the past, the perception of one of the saddest chapters in Czech history changes. More and more young people have not experienced it, and for older people the period is becoming the background of the fond memories of their youth. This change in the perception of the Communist era is perhaps best illustrated by the changes in the perception of Fred Kramer’s fashion photograph of the five women models in front of the Sjezdový palác in Prague (on the cover of the present volume). Whereas twenty years ago, probably most people here would have considered it, in comparison with the superb contemporaneous fashion photos by Richard Avedon or Irving Penn, to be totalitarian kitsch, today, it exudes the charm of the unwanted, standing as a gentle reminder of what things looked like in Czechoslovakia, once upon a time in the East.

Vladimír Birgus and Tomáš Pospěch

(Translated by Vladimíra Šefranka and Derek Paton)